29. 04. 2022

A little confession: I like to play video games, perhaps surprisingly often. For the purposes of this article, I tried to recall all the games I had either finished or at least spent a lot of time with. I was surprised myself that I was able to put roughly 60 plays on the list. In fact, with an average video game, a person spends perhaps 20 hours to finish it, and can drown 10- to 100-fold more hours in online multiplayer games. And those are just the games that I've spent a lot of time with, if I were to include all the games that I've just tried, the number would easily go up tenfold or up. Am I really drowning this much time?

It's still a little hard for me to admit to myself that I spend so much time with video games, and it's even harder to tell someone else, or even in public. Maybe you feel the same way: when you mention video games, I kind of expect this activity to be met with condemnation as a simple waste of time, an addiction I can't forgive, or even a sin. I don't want to hear this reaction, so maybe I'm talking about the books I'm reading, and I can be sure that I'm not going to get a similar condemnation, instead it might be the seed of a stimulating debate. And maybe I'm still prejudiced against myself that video games are just a waste of time.

Note: nolifer from the Latin noli- (nothing) + fer (wear), or man who carries no meaning, someone insignificant. Cf. lucifer.

But when I think about it rationally, I don't really understand it. Movies, a medium in something akin to video games, are treated as something overwhelmingly entertaining, but on the other hand, there are prestigious awards for best films like the Golden Palm of Cannes-game awards may be so The Game Awards, but they are not such prestigious awards and nobody knows them. Sure, some movies are appalling, but we still think of movies as art in general, and when someone says they're interested in movies, that means they have a cultural perspective. When someone says they have an eye for video games, most of the time we imagine a nolifer living in a basement.

And yet the very shape of some video games is often not very different from movies. In games like Call Of Duty, we find cinematic cut-scenes, gameplay tends to be adapted to maximize spectacle and the player barely has a chance to die. Other games from the so-called visual novels genre are more like books, their player spending almost all his time reading some text. Yet players are almost never thought of as culturally conscious readers, prizes for literary work were not common in video games until recently (but this is changing, for example, there is a Nebula award with a category of best game writing, or Hugo award).

In fact, video games very often adopt artistic techniques from other media. Nevertheless, this blurs the very line between art forms. Then why such a dishonor? It's as if some works are given the label of a video game as something inferior.

In Disco Elysium we find ourselves in the role of a detective solving a murder case. The player here moves in a 2D space, but his main way of interacting with the world is reading text and selecting options. In this game, it's more like a book or a gamebook.

I think the inferiority of video games has to do with gaming and gaming culture. Without question, this culture contains certain toxic elements, as well as simply failed games. On the other hand, video games have given me some of the most unique experiences I've had in my life. That's why I'd like to help give this medium the confidence to reach its full potential. So that people value video games for their artistic quality, and video game makers also focus on that quality (as opposed to just making a profit).

So in this article, I would like to think about what gamesmanship is today, how we perceive it today, and which influences shape it. First I think about how to look at Gammer culture properly (what distinguishes it from literature, perhaps), and then I focus on the main things that bother me today. It seems to me that we are stuck in one place and need to go somewhere else: that is why, in (possible) other articles, I intend instead to praise the games and pick up potential new directions that the games can help us take. I am willing to lend myself to a bit of madness and impetuosity if this will allow us to see even a glimpse of another world.

I still feel there's a certain gulf between those who play video games (gamers) and those who don't. I am writing this article so that both groups can take something from it, if possible.

When we analyze a cultural phenomenon of which we are ourselves a part, it can be easy for us to overlook important aspects of a thing that we consider normal because we are used to it. So I'll introduce a few analytical tricks or tools to make the job easier, I found in The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games by Christopher A. Paula.

Jim Stephanie Sterling well describes the controversy over git gud in games from From Software here.

First, there is a widespread perception in the gamer community that some games are more authentic or genuine than others, often depending on which game is harder. Evergreen is a perpetual argument between whether the better MOBA game is League of Legends or DOTA (MOBA is one particular type of game: multiplayer online battle arena). Similarly, the Dark Souls and Elden Ring series of games are also being discussed. Their difficulty often discourages new players, which the community literally makes gatekeeping: if you can't play Dark Souls, you don't have skill and git gud [get good]. But not only that, even players who play Dark Souls well but don't use the gambling community's preferred meelee style of fighting are often oppressed because distance fighting is said to be cheating and only done by pussies.

The very dark world of the game Dark Souls 1 seemed to be telling the player he wasn't welcome. But in reality, the world has been created by game designers in an unprecedented way, so that most players will love it and feel at home in it. Likewise, the system of combat may seem too complicated, but there is an underlying methodology that allows players to improve. Dark Souls is simply a well-crafted game and would benefit from less community gatekeeping.

There is also the widespread idea that mobile games are not real games, or that games on certain types of consoles are not as good as those on other consoles or computers. It is relatively simple to avoid obvious instances of discrimination, but we can still succumb to some more hidden case. Therefore, let us be as inclusive as possible in terms of the Games, but also broaden our conception so that it does not focus solely on the Games themselves. I quote directly from that book (translation proper, p. 68): Putting games at the center of our attention leads to attempts to understand everything through games rather than seeking multiple diversionary perspectives or pursuing other areas, cultures and activities for inspiration and context. This then puts those within that culture in a limited position where it becomes hard to think of things outside the game and where we define all things according to how they fit into games [even when describing real events with a clearly important non-video game context].

By acknowledging the multiplicity of ways that people can integrate into video game culture, we can go one step further. In fact, specifically for video games, co-creativity often applies. The game's form is shaped (or rather co-shaped) by its players: in Minecraft, players are attracted to the structures they build themselves; in massive multiplayer games (MMOs), gameplay often fades into the background before the interactions of individual players and the creation of a gild. Games here function more as tools to ease the passage of creativity (one category is sandboxes, the screenshot of one is below) or as virtual locations in which we meet.

Games like sand:box (screenshot from this game) rank in the sandbox (sandbox) genre, when there is no clear goal, and the player is only supposed to experiment with the rules of the game. The content of the game is then made up entirely of the player, but using game rules. Of course, games can have elements of a sandbox like the game NOITA, where you can experiment but you also have a purpose. Sometimes the game isn't even sandbox according to the developer's intent, but the players make it sandbox: for example, by using glitch in Pokemon Yellow you can ignore all the rules and you basically have a sandbox. Often sandboxes also arise as mods (programmed modifications) of certain games, which is the case Garry's Mod.

But, along with the assertion that the boundaries of artistic genres intersect, we conclude that a degree of co-creativity is present in all art forms. For example, the cardinal rule of postmodern literature is that its reader is also a co-author, for he gives meaning to the text through his interpretations; but, equally, in the architecture of public spaces, we must be mindful of which people inhabit the space and what they use it for - a work of art is not only an architectural element, but also how it fits into people's daily routines, and how people transform it for their own needs.

What a horrible gall! Video-video culture doesn't just include gaming, it also has to include all games, even those that straddle genres. At the same time, because of co-creativity, the player is part of the game, so what are we talking about?

You can simply get lost in it if you focus on the petty. However, in order to really analyze video games, we need to view them in such a holistic way (i.e., as an interwoven whole) and post-modern way (i.e. rhizomatically, that the whole has no beginning and end, and we perceive only the interconnection of individual aspects). Maybe not to talk about video games at all, but video game insight into art in general.

I think it's worth trying to adopt this outlook because it will allow us a more comprehensive understanding of the subject. This understanding can give video games respectability and thus boost their overall perception. But ultimately, we don't try to understand video games and give them respectability just for the sake of the games themselves, that understanding will help us in other parts of our lives (by learning to use the video game preview and then using it on anything as it comes in handy).

I don't like artworks to be compared and there's some competition between them. Still, I say with no shame that a lot of bad games are made these days. For 2021, the video game market size was 85.86 billion (for comparison, film was less than half that even before the pandemic), with almost 11,000 new titles added to the largest video game platform, Steam, in the same year (a similar number of new movies were added to IMDb # #). With so much money and quantity, it's just clear that many video games (and movies, too) will be cashgrabs and only cashgrabs.

It may even come as no surprise to say that many of the most profitable and popular games have very little artistic value and exist only to extract money from their players. Games have developed surgically accurate tools for fleecing players out of money, targeting, say, neurodivergent people or children who are hard to defend. Exactly in the presentation Let's go Whaling...

The development of the Prince of Persia was intriguingly influenced by the lack of memory on the computers at the time; yet advanced graphics using the so-called rotoscopy were managed. More here. The game is available now, for example, on Arch Linux you just download the sdlpop (github) package.

These specific tactics of specific video games fit into broader patterns. I'll describe three of these patterns: meritocracy, digital work, and a toxic environment. Of course, these formulas are somewhat arbitrary: I will describe them primarily so that we don't stray too far from the concrete in abstract debates. My ultimate goal is to describe how these patterns fit into a holistic video game concept.

Before we begin: how can we discover patterns in video games? Most of the time, we can pick up on certain immutable elements that we keep seeing across video game culture (and they can be symbols, speech patterns (rhetoric), etc.). Subsequently, we have to interpret these fixed elements, thus explaining a more general pattern.

One very typical motive for video games is that of trying: already historically, video games have mostly had to be won, and that meant having to go through a lot of levels in a short timeout (as in the legendary Prince of Persia), defeating a lot of enemies as in Space Invaders or demonstrating some ability to navigate and solve problems as in Legend of Zelda (Of course, it would be possible to approach the analysis differently and choose a different motive).

A diagram describing how I analyse games. First, I notice some phenomena, which I then describe en masse using formulas (in terms of patterns, not formulas). At the end, however, I have to ask if, for example, we could do a different formula selection and what the formulas tell us about the games.

The motive for the effort gradually took on new and new forms: the effort and skill could be demonstrated in tournaments, for example in games like CS:GO a person has to shoot his enemy and his score is traditionally represented by K/D/A (kills, deaths, assists), with the ratio of kills to K/D determining how good you are. This system has spread to many games, including League of Legends. What's important here is the direct comparability of who's how good, and this has allowed a very competitive culture to emerge.

For a better understanding of the meritocracy issue, I recommend Michael Sandel's The Tyranny of Merit.

The culture of tournaments and pre-tournaments causes a lot of exciting moments and certainly has its virtues. Nonetheless, we can criticize it as inherently meritocratic. This means that a person's worth in these communities is determined purely by how good they are at the video game. And when I write value, I mean literally value in the most myopic sense. Although on the face of it, that may sound good because it gives everyone a chance to break through.

But all meritocracy is a fa\u00e7ade: people are not fairly assigned value, but harsh judgment remains. For example: not everyone has a chance to practice that many video games, depending on their background. Maybe that's why we see so many white men (and no women) on the rungs of tournaments even now. Secondly, the Gamer community carries a lot of resentment, targeting people who cannot defend themselves. A lightweight example might be a video about the player HungerBox from the Super Smash Bros Meelee game, for something more raunchy I recommend opening the second chapter of the first recommended book, The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games, about the gamergate case. Third, I wrote that the gaming community includes people who don't play directly. But they tend to be ousted because they don't demonstrate skill.

He's crossed bayonets, lava and circular saws make the Super Meatboy game one of the most challenging platformers. But the game shows that players with previous experience of a similar genre (e.g., the Super Mario Bros game with the same initials) will have much less of a problem with it and will go further than regular players. Fortunately, SMB doesn't mock the player for failing -- it promotes persistence by how short the respawn timer is. Moreover, the difficulty curve of this game does not rise as quickly, so players of all abilities will find levels with adequate difficulty for them.

The constant pressure to win can often be devastating, and gaming companies often exploit it to build addiction in players (a player who cannot stop playing the game because of addiction is the best customer). I'm not making this up, EA (Electronic Arts) filed a patent in 2016 explaining how it collects player data, analyzes it through machine learning, assigns players their player profile based on it, and the player profile determines who they play against. You can find more detailed information in this thread on Reddit. True, the operation of EA and other gaming companies is highly opaque, but we have sufficient reason to believe that the matchmaking systems are developed, and in force.

For example, every LoL player knows about the smurf queue, so why wouldn't Riot Games use a similar manipulation on the matchmaking of the remaining players? Especially when the same company is known for creating a K-pop band out of their game characters and purposely using those fake idols to try to create parasocial relationships in the players to continue the game. This involves copying the latest trends, so this company also practices queerbaiting (that is, some virtual influencers act like they're queer to get sympathy from queer fans, however they're never queer openly so that conservative fans don't notice it and get annoyed). So LoL has no problem using morally dubious tactics to squeeze as much money out of its players as possible-being a public limited company, it is even legally obligated to generate as much profit as possible.

To meet the world of World of Warcraft, I recommend video from the Folding Ideas channel.

The motive for the effort has also spread to another genre, where it has taken a very different form: I'm talking about massive multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs). One example of this game may be World of Warcraft. Here the endeavour manifests itself as regular work (in terms of wage labour). In fact, MMORPGs generally operate differently from tournament games like CS:GO, rather virtual worlds where players can meet. Similar to the way children used to go goofing around on the estate, video games replaced this with the much more interesting world of Azeroth.

So people gather in the gaming world and fill up on various quests, like killing 20 monsters, going somewhere or picking up materials or stealing armor. Since interaction between players is accounted for, mechanically gameplay isn't that demanding: pushing the right sequence of keys requires no dexterity, unlike tournament games. Skill players are tested differently. On a social level, players must be able to co-operate and cluster into functional groupings called Guilds. If they don't, their progress in the game is significantly slowed down (and it's not fun, either). The second skill check is in the knowledge of the game: you have to know where to go to get the most money for your time, or know which armor to buy to be the strongest.

However, even with the greatest optimization of the game, it still takes time to get to the higher levels. And the time the player spends on it really isn't very interesting, he just clicks and his character collects wood for 5 seconds and then has to click away etc. In fact, these are such repetitive tasks that they could be automated to replace the shoes. Some players actually do it (it's called botching), but the gaming system can generally detect such behavior and incur penalties like a ban.

Players often have to repeat the same dull action over and over while playing games, their motivation being to become strong one day or to get something interesting: such dull repetition is called grinding. It puts us in a situation where the target of a video game is somehow artificially hidden behind a time barrier. Of course, good video games are still fun from moment to moment, but there are really few such video games, most can't avoid grinding, and it gets pretty boring.

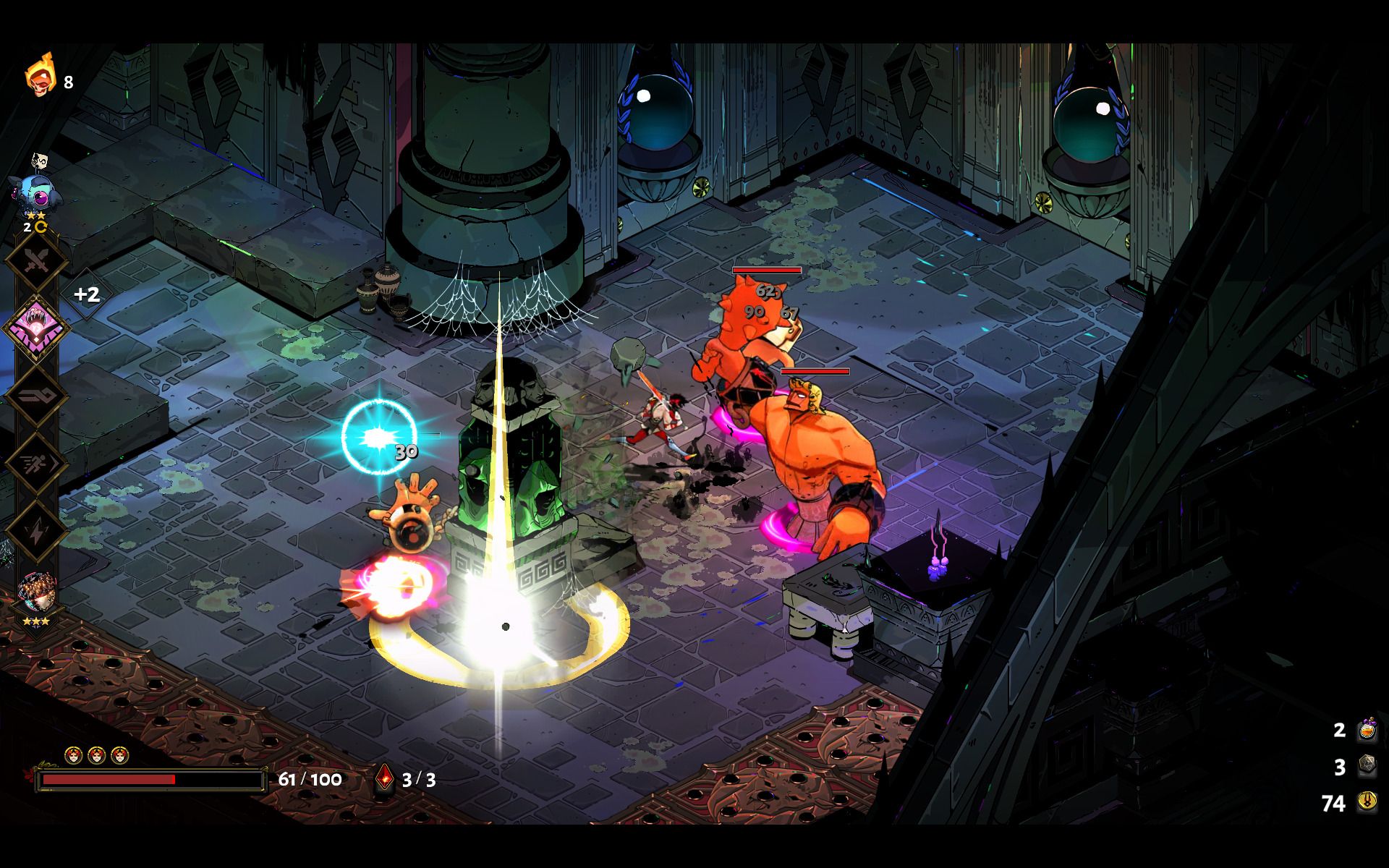

There are aspects of grinding in Hades: it takes many hours to unlock some abilities. But the game counterbalances this by saying that gameplay is always fun, not repetitive. In addition, the game uses a unique system of dialogue (in some ways resembling dating simulators) to focus the player on getting to know the game characters rather than on self-improvement.

About how resources in every game can be understood as economics made by video channel GMTK. The only question is whether it's productive to view every game as an economy, and which way it can carry designers.

Computer games containing grinding mostly have their in-game economics (and some games like Wakfu even the ecosystem). There is a market for items that players can sell or buy from each other. Playing video games can thus turn into a literal job/job, where you grind an activity that doesn't really interest you to get an in-game object that also has a real value converted into dollars. That's why players have no problem paying real money for objects: they figure that in their real work, they'll make them faster than they can by grinding.

Flipping work to the virtual world is what Meta wants to do with its meta-version at the moment: we can hope that it will fail, because this new way of working is not yet regulated at all, and we can hardly hope that it ever will be. The world of cryptocurrencies, for its part, is trying to implement another aspect of the work: speculating in markets. In MMORPGs there are gaming markets where one can sell and buy. Indeed, there are speculators trying to control such markets. For example, CS:GO is so notorious for the gun skinny shop. But crypto-machines have only taken this concept without an attached game, and are trying to impose it on humans. The whole issue, including for example the work of digital slaves in the Philippines, is described by the Folding Ideas channel here.

Just long enough to play some multiplayer online game and you're sure to get insulted, even more so if you're a member of a racial minority, a woman, or have a disability. If you play games regularly, maybe you're used to this kind of behavior. If not, you probably suspect something about toxicity, but you don't know the full extent of it. In any case, I would like to show that toxicity is not a problem of a few bad players, but a recurring problem across video game culture (examples I mostly take from The Toxic Meritocracy of Video Games).

One of the most common formats of the game is the PvP deathmatch, or Player vs Player, where players have to kill each other. And most often with shooter PvP games like Battlefield, Halo or CS:GO, many toxicities occur. I don't play this type of game often, so I don't have that insight into it, but games cause players to get mad at each other and then vent their anger with profanity.

Swearing can come via chat (font) or is directly voice-chat in some games, so players can yell at each other on live TV. Perhaps a certain level of profanity is to be expected, however certain tips of profanity prevail in video games: it is common to swear at players based on their nationality alone, for example in CS:GO to Russians and in LoL to Poles. Also, people are often told that they're retarded, that they're gay, or that they're kids. I have nothing against swearing as such, but the profanity referred to above is involved in a racist, ableist and homophobic environment, being just one piece in the puzzle that I will describe further.

TW: rape (to end of section)

Even in video games where it is not possible to (voice-)chat, there are problematic behaviors. For there is a widespread practice of so-called teabagging, where after a player kills someone, he walks up to his corpse and repeatedly squats on it, disgracing his body. You may find this funny, but this insult is no doubt sexually charged, and I think it's another manifestation of sexism in video games. Similarly, it is widespread for players to say of others that they have been raped (rape) when they are beaten or raped. If you don't believe it, write \I got raped in X PvP\ on Youtube, where X is the name of any game. For all the games I've tried, I've found at least some results, and that's to be expected to delete similar Youtube videos.

It may seem to you that the phenomena in question are merely the misconduct of individual players. Yet there are many documented instances of sexism occurring in institutions of video-game culture in leadership positions in the open. Maybe at the PAX East Dickwolf conference, they published a comic book with a rape joke, and after people complained, they published a merch that made fun of the protests. At the E3 conference in 2013, the main organisers also made a \joke\ about rape, portraying as the victim a woman who didn't play video games.

And this problem is found in professional gaming, or E-sports. Especially in fighting games like Tekken, sexual harassment is widespread, many cases reveal a simple DuckDuckGo search. But it also speaks to the deeper embedding of the problem in the community that in most professional E-sport teams of any game, there is not one woman, though there is no reason why women should be worse than men at games.

So, based on these examples of toxic behavior in video games (and many more could still be traced), I argue that video game culture often fosters a toxic environment, that systemically (i.e. at system level) it causes or enables abuse of many minorities and groups of people who cannot defend themselves.

Celeste proves that toxicity does not have to be inherently present in video games. In addition to the general feel-good atmosphere and queer inclusiveness, I chose this game to highlight a different kind of competition from PvP deathmatch: speedrunning. The Speedrunners try to beat the game in as short a time as possible, and they compete in that. This type of rivalry has a low entry barrier because speedrunners can be used for every game and the less well known, the less competitive. Also, there is no constant insulting of opponents, plus players can compete separately from others, which protects them from harassment. If you're interested, you might as well watch GDQ speedrun Celeste.

So I've named three negative patterns of phenomena that I observe in video games, and now it would be great to come up with a simple explanation to explain them all. And for some people, that explanation is the capitalist way of producing video games. The economic dimension is certainly important for video games. On the other hand, video game culture is not just video games - we have to approach games holistically, and therefore our explanation must not stop with the abuse of capitalism. But since many video game critics (like Jim Stephanie Sterling) complain about capitalism, I will make their case for clarity -- they are not completely worthless.

That is: the companies producing the biggest video games are market-based, and as such are legally required to maximize their profits. It makes sense for them to practice things on the edge of the law. One example is predatory lootboxes (lootboxes are essentially deregulated gambling) bringing in money. Returning players also provide a steady stream of revenue, which is why it makes sense to try to create addiction in players, or to convert their games into regular work.

When mentioning schools, I must not forget that they are hierarchical institutions that we force children to attend and they do not have the possibility of agence (e.g. choice of subjects). Schools often function as instruments of cultural genocide. More under the term Youth Liberation.

Which way can this trend take us? First, gaming itself is becoming a brand in its own right: gamer keyboards, desks, gamer web browsers, and even obscure things like Babica's cooking show Ich bin ein gamer, are being sold.

Second, we are seeing the popularization of the concept of gamification, or the delivery of video game elements where they have not been before. Companies use this to create an emotional attachment or, worse, an addiction to their product. Examples include supermarket apps and Bill's teddy bears, promo video games, or gamification at work that employees themselves have to endure. You can listen to this slightly techno-optimistic TED lecture. Of course, the games aren't necessarily wrong (after all, J. A. Komensky promoted the school concept with a game, and the idea has value), only companies use it as a tool of exploitation.

Here I would like to stress once again that we must not be naive and reduce all the bad aspects of gaming to manifestations of capitalism. For example, patriarchal tendencies in gaming manifested by people laughing at women for not being able to play cannot be explained by monetary incentivism. And they lead to, for example, a high rape culture in Activision Blizzard, Ubisoft, etc., according to the familiar pyramid of violence.

So some video games have turned into a vicious contest, where the one they play loses, while others have turned into work, only digital. Also, toxic behaviors abound across video game culture. How do you explain that?

Inspired by The Toxic Meritocracy in Video Games, I offer a very straightforward explanation. I don't think that video games alone incite violence, nor do I believe other far-fetched conspiracy theories, but I like to think of it in a more prosaic way: video games are simply played by ordinary people with all their peculiarities, and so their bad side is reflected in video games. For example, sexism and patriarchy existed in society before video games existed; video game culture provided only additional space for their dissemination. Similarly, it's with meritocracy, or boring and frustrating work.

So I say that it is not fundamentally new that is behind the toxic aspects of video game culture, but the recycling of something old. In fact, this flipping of old toxic phenomena into the video game space hampers innovation, because old things appear to be new, and so are hard to get rid of.

From this perspective, I have some fairly easy-to-articulate advice for the healthy expansion of video game culture: let's finally make something new. And a new one, not in the sense of extending already existing phenomena, but something much crazier. For video games allow us to reach into hitherto unthinkable worlds, that is their main preference: let us use it.

Another world is possible.